Analogy Fact Check #1: Owning the Mona Lisa

Coming out of the (broom) closet.

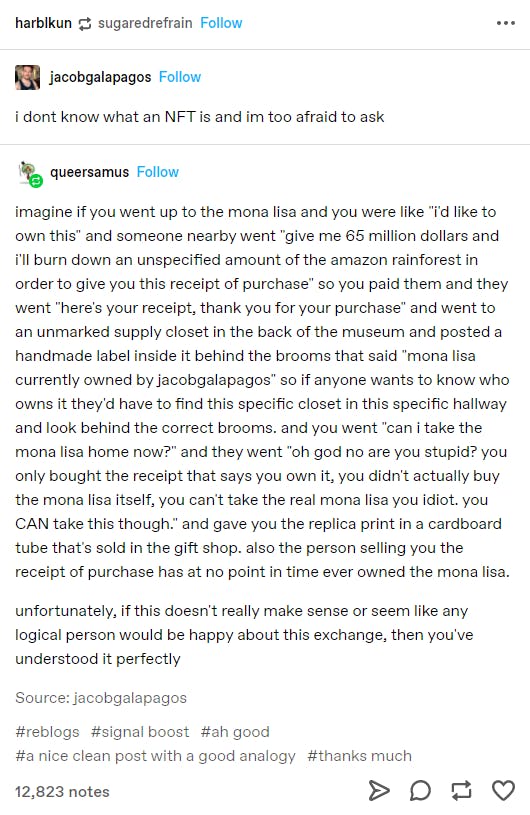

Among the many threads on social media where people who are alien to the concept of NFTs are asking what this fancy new three-letter thing is, one particularly popular explanation seems to have become quite a go-to analogy. It appears to be from a Tumblr-style thread and it's quite a read.

I don't know if it's deliberately trying to sound convoluted from a poor understanding or whether the explainer is legitimately confused themselves. From saying that the alleged seller would "burn down an unspecified amount of the Amazon rainforest" shows a poor understanding of the energy consumption of EVM-compatible blockchains that can support NFTs. While energy is consumed by these blockchains for the minting and trading of NFTs the comparison to burning down the Amazon rainforest is blown severely out of proportion but the details of that is a story for another day.

However, they chose an excellent example to explain what an NFT is.

image from Pixabay

The Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci is not just one of the most valuable paintings in the world, it's also among the most reproduced images in history with plenty of lookalikes and reproductions of the original by painters, forgers and artists alike. However regardless of how many iterations existed, the original Mona Lisa has, for centuries, been property of the French state.

The painting is on display at The Louvre Museum in Paris which is also run by the French Government. This is an arrangement where its ownership can be questioned. Does it belong to The Louvre? Does that mean that whatever belongs to The Louvre is automatically property of the French government?

Traditionally we would slap our name on something we own to assert our ownership over it but in the case of art, many would rather not damage or alter the pristine state of the artwork just so that an owner's name can be put on it. Furthermore that name would need to be altered when the artwork changes hands.

One common solution is to have a document certifying ownership. This is typically in the form of a Title Deed or a document that certifies that whoever holds it is also the owner of an item it is referencing. Cars, properties and some articles of jewellery often have such documents to certify their authenticity and ownership. They are usually countersigned by government authorities such as the land office or Department of Motor Vehicles where they can be checked against.

Let's pick up this Analogy where the writer queersamus explains that after someone offered to let you purchase the Mona Lisa, they would 'go to an unmarked supply closet in the back of the museum' to post a handmade label inside of it to state that you are the owner of the Mona Lisa.

Such a label would be pretty damn useless, just like an NFT minted in the same manner - referencing an artwork that was not meant to be tokenised or tokenised without the consent of its creator/present owner.

However, the explanation of the location of the label being in an unmarked supply closet is misplaced. The blockchain is not an unmarked supply closet. It's not a single location as its replicated across its network which makes it both searchable and immutable.

On top of that it is also public and digitised, meaning that NFTs are searchable and publicly viewable. The importance of this is that it's not an obscure, single record. A blockchain that hosts NFTs like Ethereum keeps this in its history. Even if the NFT is destroyed by its owner through a burn command (enabled on some NFTs), the record of its existence is eternal - a broom closet is anything but that.

This in no way adds validity to the aforementioned hypothetical Mona Lisa NFT. This is to point out a misconception of how an NFT is stored and accessed and how different it is from physical document storage and present day computer filesystems.

Of course The Louvre is under no obligation to let you redeem the actual Mona Lisa for some NFT you bought from a stranger. This is where the analogy is spot-on. NFT issuance is traceable on the blockchain to the address of its issuer. This means that if the French government by some stretch of the imagination really wanted to sell you an NFT of the Mona Lisa, they can identify that the NFT proving the ownership of the painting originated from themselves and choose to honor it.

Whether they do so or not is a different story since we are dealing with a physical, real-world object here. The technological implication changes significantly when the artwork in question is completely digital and intangible. In that case, of course you can just right-click and save the artwork onto your laptop and you potentially have a perfect 1:1 copy of the digital artwork and not a gift shop replica like the one mentioned in the analogy.

This explanation makes sense because one - an NFT is a certificate in this context and in this case, is trying to be a certificate of ownership of the Mona Lisa. What should have been explained that this is an abuse of the technology and not its intended purpose of being a certificate. Just like how counterfeit certificates can be made in the real world, counterfeit certificates can be made on the blockchain. The difference is each NFT can be traced back to its issuer - and an issuer can elect to only honor the NFTs that they issued.

While counterfeit certificates can be made, it is next to impossible to impersonate an issuer. You can make a phony NFT but it will always come from you and never from who you're trying to impersonate. Hence there needs to be this distinction between a counterfeit and a forgery. You can easily counterfeit an NFT but forging an NFT is practically impossible.

What queersamus got right in this analogy is that an NFT is indeed just a certificate of ownership that is not necessarily always issued by a genuine authority and in this case, is completely bogus. People do sell such NFTs as part of scams to make a quick buck - and the authority that controls the actual item that the NFT claims to certify ownership of need not respect the NFT because the issuer it is traced to is not identifiable by them, hence the part about trying to take the original Mona Lisa home and failing miserably, possibly at the hands of the gendarmerie.

One bad example does not define the technology as a whole. There are many things wrong with NFTs which is why they suck for the most part today - but one bad example should not define everything to do with it.